Moving to Trauma-Responsive Care

Butler Center for Research - April 2021

Download the Moving to Trauma-Responsive Care Research Update

Trauma comes in many forms and can include psychological, physical, emotional, sexual abuse, or domestic violence. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) describes individual trauma as resulting from "an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual's functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being."1 Traumatic events can include a host of situations involving loss and threats to safety and well-being, such as separation; natural disasters; bullying and cyberbullying; and chronic and historical stressors, such as poverty, racism, and intergenerational trauma.1, 2 The COVID-19 pandemic can now be added to this list with the impacts of social isolation and increasing death tolls experienced nationally and internationally.3,4

Many people who have substance use disorders have experienced trauma as children or adults.5, 6 Substance abuse is known to predispose people to higher rates of traumas, such as dangerous situations and accidents, while under the influence.7, 8 Unaddressed trauma significantly increases the risk of substance use, mental health disorders, and chronic physical diseases.9, 10, 11 A Department of Veterans Affairs study found that a high proportion of SUD patients had trauma histories.12 One of the first studies on addicted women and trauma found that a history of being abused drastically increased the likelihood that a woman would abuse alcohol and other drugs.13 In addition, people who abuse substances and have experienced trauma have worse treatment outcomes than those without histories of trauma.14, 15 Thus the process of recovery is more difficult, and the counselor's role is more challenging, when clients have histories of trauma.

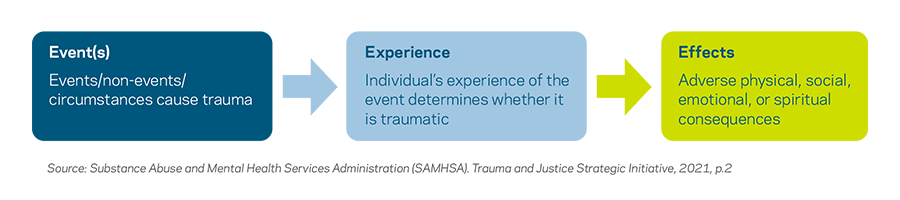

Trauma is a complex experience. According to SAMHSA, the experience of trauma can be described through some common elements: event(s), experience, and effects, also known as the "Three Es."1 These elements address the uniqueness of an individual's response to an event and how an event affects one's future behavior and well-being.

- An Event is objective and measurable. Traumatic events include abuse (physical, emotional, sexual), domestic or community violence, an accident or natural disaster, and war or terrorism.

- An Experience is subjective and difficult to measure, because it relates to how someone reacts to an event. It is often thought to be life threatening or physically or emotionally overwhelming, and intensity can vary among people and over time. The way one person experiences an event might differ from the way another person does; culture, gender, and age all influence one's experience of the event. Resilience, risk and protective factors, and supports may contribute to this experience.

- Effects are the reactions a person has to an event and the ways an experience changes or alters that person's ongoing and future behavior. Classic symptoms include experiencing hyperarousal, such as overreacting or being hypervigilant; re-experiencing an event as nightmares or flashbacks; and avoiding a situation by having a fight, flight, or freeze reaction. The effects of a traumatic event can have a long-term impact on neurobiological development and contribute to negative physical, hormonal, and chemical changes due to stress responses.

It is important to recognize the pervasiveness and impact of trauma on survivors, staff, organizations and communities. The need to address trauma is increasingly viewed as an important component of effective behavioral health services.

Trauma-Informed Approaches

Interest in trauma-informed approaches has grown substantially. These approaches are characterized by integrating an understanding of trauma throughout a program, organization, or system to enhance the quality, effectiveness, and delivery of services provided to individuals and groups.16 Trauma-informed care has been used in a variety of settings, including criminal justice, school, child welfare, and health care systems.

Although there is not a universal definition of trauma-informed practice, the core tenets are reflected in the SAMHSA's concept. In a trauma-informed approach, all people at all levels of the organization or system have a basic awareness about trauma and understand how trauma can affect families, groups, organizations, and communities as well as individuals.1 According to SAMHSA, a program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed:

- Realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery

- Recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system

- Responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices

- Seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.1

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) has been at the forefront of efforts to raise public awareness of trauma and trauma symptoms, and to develop and promote the use of evidence-based trauma screenings and interventions. Among its important contributions, the NCTSN has provided guidance to organizations and larger systems (e.g., child welfare, juvenile justice, education, and workforce development systems) about the ways they can provide trauma-informed care and become trauma-responsive organizations. Recommendations center on integrating research and practices that infuse knowledge of culturally responsive screening, assessments, and treatment approaches. They also include efforts to strengthen resilience and protective factors in clients and client populations, ensuring a continuity of care and collaboration across systems, including addressing symptoms of secondary trauma in frontline professionals.17

Trauma-informed practices can equip behavioral health service providers with the knowledge and skills to meet the specific needs of clients, recognize that individuals may be affected by trauma whether acknowledged or not, and understand that trauma likely affects many individuals seeking help.

Moving to Trauma-Responsive Care

Knowledge and awareness of trauma is a necessity, but in order to fully meet the needs of people who have experienced trauma and adversity, a more significant level of responsiveness to those needs must be achieved.18 Much of the focus thus far has been on trauma-informed treatment and individual providers who use trauma-informed approaches. There is a recognition that trauma-responsive care services also need to incorporate an organizational climate that is sensitive to those with trauma histories, and recognition that the quality of services delivered are impacted by the organizational culture in which service providers are employed.19 Trauma-responsive models and frameworks have been developed for several systems including child welfare, medical, criminal justice and school organizations, but research has not shown the same effort in the addiction field. The states of Missouri and Massachusetts have begun the move to becoming trauma-responsive systems, rather than remaining more narrowly focused on only trauma-informed treatment modalities or trauma-informed care providers.

THE MISSOURI MODEL (FOR SCHOOLS)

The implementation of a trauma-informed approach is an ongoing organizational change process. Most people in the field emphasize that a trauma-informed approach is not a program model that can be implemented and then simply monitored by a fidelity checklist. Rather, it is a profound paradigm shift in knowledge, perspective, attitudes and skills that continues to deepen and unfold over time.20

Trauma responsivity is the point at which planning and action take place and procedures in all systems (cafeteria staff, transportation staff, administration, teachers, etc.) are reconsidered with the intent to better accommodate those with trauma backgrounds. Staff is better supported through self-care support, supervision models, staff development, addressing of staff trauma, and performance evaluations in the trauma-responsive stage. Staff begins to more concretely apply trauma foundations to their behaviors and practices in their specific roles. Language is embedded throughout the infrastructure that corresponds with safety, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and empowerment. In trauma responsivity, universal screening for trauma takes place, and trauma-specific assessment and treatment are offered to those who need them, either at school or work or to an outside referral. Additionally, there is a predetermined plan in place for crises that reflects trauma-informed values.20

THE MASSACHUSETTS CHILDHOOD TRAUMA TASK FORCE FRAMEWORK

The Massachusetts Childhood Trauma Task Force has decided to adopt the term trauma-informed and responsive (TIR) to describe approaches that are both informed by the research on trauma and child development and responsive to the needs of children and their families who have experienced trauma. Specifically, to be Trauma-Informed and Responsive (TIR) means that:21

- Adults working with children, youth and families realize the widespread impact of trauma on child development and behavior; recognize and respond to the impact of traumatic stress on those who have contact with various systems, including children, caregivers and service providers; actively work to avoid re-traumatization; and take an active role in promoting healing; and

- Organizations infuse an understanding of trauma and its impacts into the organization's culture, policies, and practices, with the goals of maximizing physical and psychological safety, mitigating factors that contribute to trauma and re-traumatization, facilitating the recovery of the child and family, and supporting all children's ability to thrive.

The Massachusetts Childhood Trauma Task Force has developed a framework for trauma informed and responsive organizations in the state. The framework includes five Guiding Principles: 1. Safety; 2. Transparency and Trust; 3. Empowerment, Voice, and Choice; 4. Equity, Anti-Bias Efforts, and Cultural Affirmation; and 5. Healthy Relationships and Interactions.21

Implementing a Trauma Informed and Responsive approach requires change at multiple levels of an organization and systematic alignment with the five key principles noted above in each of the following Domains. How an organization applies the guiding principles in each domain of implementation will vary depending on the role, responsibilities, and purpose of that organization.21

Domain #1: Organizational Leadership

Leaders must actively demonstrate their commitment including leading by example, modeling healthy relationship behaviors, invite staff input as well as client input into organizational decision-making, be visible members of the agency/organization and community, and tend to their own self-care. Leaders can also prioritize the financial and time investments needed to implement trauma-responsive approaches. Leaders should strive to ensure that staff at all levels of the organization, as well as organizational materials, represent the diversity of the community being served.

Domain #2: Training and Workforce Development

Building an organization's workforce should include encouraging diversity, equity, and inclusion in hiring and promotion practices at all levels; providing training on trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and racism/equity to all employees and volunteers on an ongoing basis; developing policies that address secondary traumatic stress to prevent staff burnout that can lead to disengagement; and providing support for all levels of the workforce that includes self-care strategies and mental health benefits. Organizations should strive for adequate staffing levels and manageable caseloads.

Domain #3: Policy and Decision-Making

Policies and procedures establish expected norms of behaviors and decision-making protocols. TIR policies and procedures recognize that many of their clients, as well as in many cases the staff themselves, have experienced trauma in their lives. Policies and practices are clearly articulated, identify clear roles and responsibilities for staff members, and detail expected behavior with regards to confidentiality.

Domain #4: Physical Environment

TIR physical environments are designed with the needs and abilities of the individuals using the space in mind, and are regularly re-evaluated with input from youth, families, and staff members. Aspects of the physical environment to consider include: lighting and color; noise and smell; temperature; direct access to exits; images (e.g. on posters, in magazines); language accessibility; respect for the diverse needs (e.g. cultural, linguistic, gender, religious) of clients; and a clean, inviting, and healthy atmosphere for the staff as well as clients.

Domain #5: Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)

Implementing a TIR approach can be challenging, and organizations will likely need to reassess and modify their course of action over time. Organizations should develop written processes for regularly assessing the design and implementation of policies, programs and/or practices to ensure they are having the desired impact. Organizations should consider identifying specific, desired outcomes that are meaningful in the organization's setting and sector, and selecting methods for measuring the extent to which these outcomes have been achieved.

The models presented above are useful examples that can inform the development of trauma-responsive approaches in addiction treatment organizations.

Summary

Trauma impacts survivors, staff, organizations and communities. Addressing trauma is an important component of delivering effective organizational services. Increasing knowledge and awareness of trauma and moving to implementing trauma-responsive practices is critical in providing behavioral and addiction treatment and services, particularly with those from marginalized communities. While trauma-responsive models and frameworks have been developed for use in several systems—including child welfare, medical, criminal justice and school organizations—implementation and research in the field of addiction seems to be lagging. With a strong body of research showing that trauma greatly increases the risk of substance abuse and impacts outcomes of addiction treatment, the future of addiction treatment will necessarily integrate trauma-informed and trauma-responsive approaches to care.

The Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation Experience

While many organizations are trauma-informed, becoming trauma-responsive means looking at every aspect of an organization's programming, environment, language, and values, and involving all staff in better serving clients who have experienced trauma. The Moving from Trauma-Informed to Trauma-Responsive program, available through Hazelden Publishing, provides program administrators and clinical directors with key resources needed to train staff and make organizational changes to become trauma-responsive. This comprehensive training program involves all staff, ensuring clients are served with a trauma-responsive approach. Developed by leading trauma experts Stephanie S. Covington, PhD, and Sandra L. Bloom, MD, this program is an excellent primer to assist organizations in becoming trauma-responsive prior to implementing an in-depth trauma curriculum.

At Hazelden Betty Ford, our focus in residential and individual outpatient treatment is to provide integrated addiction and mental health services, which help patients identify trauma that can be contributing to their substance use and other co-occurring disorders.

Hazelden Betty Ford prevention solutions also focus on the early identification of and support mitigating trauma in youth. The Building Assets, Reducing Risks education model allows schools to be the first and most frequent point of contact for youth with trauma. Learn more at Barrcenter.org

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/ files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. (2020). cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

- Heath, C., Sommerfield, A., & von Ungern-Sternberg, B. S. (2020). Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75, 1364–1371. doi.org/10.1111/ anae.15180

- Marques, L., Bartuska, A. D., Cohen, J. N., & Youn, S. J. (2020). Three steps to flatten the mental health need curve amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression & Anxiety, 37, 405–406. doi.org/10.1002/da.23031

- Koenen, K. C., Stellman, S. D., Sommer, J. F., Jr., & Stellman, J. M. (2008). Persisting posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and their relationship to functioning in Vietnam veterans: A 14-year follow-up. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 49–57. doi:10.1002/ jts.20304

- Ompad, D. C., Ikeda, R. M., Shah, N., Fuller, C. M., Bailey, S., Morse, E., Kerndt, P., Maslow, C., Wu, Y., Vlahov, D., Garfein, R., & Strathdee, S. A. (2005). Childhood sexual abuse and age at initiation of injection drug use. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 703–709. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2003.019372

- Stewart, S. H., & Conrod, P. J. (2003). Psychosocial models of functional associations between posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. In P. Ouimette & P. J. Brown (Eds.), Trauma and substance abuse: Causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders (pp. 29–55). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi.org/10.1037/10460-002

- Zinzow, H. M., Resnick, H. S., Amstadter, A. B., McCauley, J. L., Ruggiero, K. J., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Drug- or alcohol-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape in relationship to mental health among a national sample of women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25, 2217–2236. doi:10.1177/0886260509354887

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of child abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading cause of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Dube, S. R., Felitti, V.J., Dong, M., Chapman, D. P., Giles, W. H., & Anda, R. F. (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. doi:10.1542/ peds.111.3.564

- Lopes, S., Hallaka, J. E. C., de Sousa, J. P. M., & de Lima Osório, F. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences and chronic lung diseases in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1720336. doi.org/10.1080/2 0008198.2020.1720336

- Ouimette, P. C., Kimerling, R., Shaw, J., & Moos, R. H. (2000). Physical and sexual abuse among women and men with substance use disorders. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 18(3), 7–17. doi:10.1300/J020v18n03_02

- Covington, S. (2007). Working with substance abusing mothers: A trauma-informed, gender-responsive approach. The Source, 16(1), 1–11. stephaniecovington.com/site/ assets/files/1532/final_source_article.pdf

- Driessen, M., Schulte, S., Luedecke, C., Schaefer, I., Sutmann, F., Ohlmeier, M., Kemper, U., Koesters, G., Chodzinski, C., Schneider, U., Broese, T., Detter, C., & Havemann-Reinicke, U. (2008). Trauma and PTSD in patients with alcohol, drug, or dual dependence: A multi-center study. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 32, 481–488. doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00591.x

- Najavits, L. M., Harned, M. S., Gallop, R. J., Butler, S. F., Barber, J. P., Thase, M. E., & Crits-Christoph, P. (2007). Six-month treatment outcomes of cocaine-dependent patients with and without PTSD in a multisite national trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 353–361. doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2007.68.353

- Champine, R. B., Lang, J. M., Nelson, A. M., Hanson, R. F., & Tebes, J. K. (2019). Systems measures of a trauma-informed approach: A systematic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3–4), 418–437. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12388

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2016). Creating trauma-informed systems. nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/creating-trauma-informed-systems

- Bloom, S. L. (2016). Advancing a national cradle-to-grave-to-cradle public health agenda, Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(4), 383–396. doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2016 .1164025

- Esaki, N. (2019) Trauma-responsive organizational cultures: How safe and supported do employees feel? Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 44(1), 1–8, doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2019.1699218

- Missouri Department of Mental Health. (2014) The Missouri Model: A developmental framework for trauma-informed approaches. dmh.mo.gov/media/pdf/missouri-model -developmental-framework-trauma-informed-approaches

- Massachusetts Childhood Trauma Task Force. (2020). Framework for trauma informed and responsive organizations in Massachusetts. mass.gov/doc/framework-for-trauma -informed-and-responsive-organizations/download