Alcohol Abuse among Law Enforcement Officers

Butler Center for Research - November 1, 2015

Links Between Officer Trauma and Substance Abuse

Download the Alcohol Abuse Among Law Enforcement Officers Research Update.

For years, many professionals in the fields of research, counseling, public policy, and criminal justice have expressed concern over alcohol use and abuse among law enforcement officers. Despite the widely held assumption that police officers are at risk for higher-than-average rates of alcohol abuse, very little research has been conducted to investigate patterns of substance abuse within the law enforcement field.1 Recent research into the relationships among social and cultural factors, stress, trauma, and problematic alcohol use has finally been able to shed light on this special population, which is, in turn, opening the doors to new, empirically founded treatment strategies.

Substance Use and Abuse Rates for Law Enforcement Officers

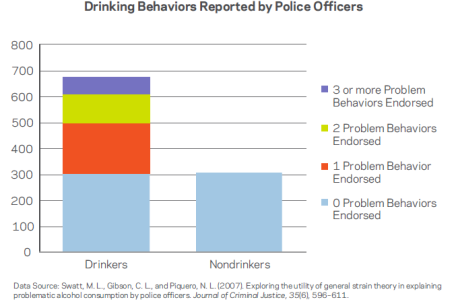

In 2010, a study of police officers working in urban areas found that 11% of male officers and 16% of female officers reported alcohol use levels deemed "at-risk" by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).1 A 2007 survey of 980 American police officers found that 37.6% of the respondents endorsed one or more problem drinking behaviors.13 Researchers have long debated the reasons for elevated alcohol consumption among police officers, but most agree that underlying patterns include social and stress-related problem drinking behaviors.2 Among social factors, drinking to "fit in" with one's peers has been identified as a significant contributor to drinking for police officers who demonstrate hazardous alcohol consumption.2 A 2001 survey conducted among police officers provides some insight as to why officers may feel the need to drink in order to fit in: 31% of those who responded to the survey reported that they believed nondrinkers "were viewed as suspicious and unsociable people" by other officers.3 Social factors are particularly important to consider among the law enforcement population, as police officers spend a very large amount of their social time with other officers. Most police officers report spending at least 25% of their social time (outside of work) with their coworkers, and 10% of officers reported that they spent 75% or more of their free time with coworkers.3 Many scientists and clinicians fear that the combination of drinking to fit in and spending large amounts of time with colleagues could lead to a culture of problematic drinking behaviors among police officers.2 While social factors are certainly a major concern, perhaps an even more significant area of interest is the relationship between the stress and trauma faced by officers in the line of duty and subsequent increases in alcohol consumption.

Links Between Officer Trauma and Substance Abuse

Research linking trauma and substance abuse began to gain momentum during the Vietnam War, when large numbers of active and returning soldiers presented elevated rates of alcohol and other drug use.4, 5 Since then, scientists have learned a great deal about the effects of stress and trauma on mental and physical health. Exposure to traumatic events can result in stress disorders, which cause serious physical, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral changes that can be very unpleasant and can cause significant problems with productivity, social and family functioning, and overall well-being.6 One of the most commonly studied stress disorders is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Recently, researchers determined that nearly half of individuals (42%) who were diagnosed with PTSD also met the criteria for an alcohol use disorder.7 It is generally believed that people suffering from PTSD and other stress disorders have not developed appropriate coping strategies for processing the stress or trauma they experience and instead turn to alcohol or other drugs as a way of dealing with their symptoms.8 As the symptoms of the stress disorder worsen over time, they are also often made worse by substance abuse. This cycle can lead to addiction, as well as increasingly severe mental and physical health problems.9

As a result of their unique occupation, police officers face a great deal of stress and trauma much more regularly than the general population. In addition to the potential for physical harm in the line of duty, officers witness traumatic and disturbing events and images and also experience stress related to their roles and reception by their community. All of these elements contribute to significant overall stressors that can result in a pathological response (e.g., PTSD or other stress disorders).2, 10 Many officers demonstrate a great deal of psychological resilience in the face of disasters and traumatic events in the line of duty, even when compared with other rescue workers (an effect attributed to tighter screening procedures and effective training for coping after a traumatic event)11. However, when nontraumatic occupational stressors (such as workload, administrative problems, or poor community relations) are present, officers exposed to traumatic events demonstrate a high prevalence for psychological distress and pathological stress disorders such as PTSD.12 The lack of availability for training related to coping strategies for nontraumatic stressors only further opens the door to alcohol consumption as a maladaptive response.9 Indeed, researchers have uncovered a strong tie between police officers’ problem drinking and the anxiety and depression that occur as a result of combined organizational and traumatic stressors.13

Special Considerations for Treatment

When available, critical incident debriefing with a trained professional has been shown to significantly reduce problem drinking behaviors following a traumatic event;14 however, research has indicated that day-to-day coping strategies aimed at reducing non-traumatic police work stressors are also critical to reducing stress-related alcohol consumption.13 Officers who seek treatment for alcohol abuse may consider exploring healthy and effective ways to address the anxiety and/or depression that may be present as a result of these daily stressors. Many police organizations offer employee assistance programs (EAPs) to facilitate treatment for alcohol use disorders. These programs are usually confidential and are also familiar with the unique struggles facing police officers, which can make them highly effective for reducing hazardous alcohol use.14, 15 Community-based self-help programs may also be of assistance to police officers, as many successful alcohol abuse treatment programs within police departments have been modeled after Twelve Step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).14 The discrete nature of AA and many other Twelve Step programs can also offer police officers protection from any perceived or actual community stigma they may fear as a result of seeking treatment.

Summary

Police officers are a unique subset of the population as a result of their occupational culture and regular exposure to stressors and trauma. These issues culminate in an increased risk for problem drinking, either as a result of social pressure or as an unhealthy way to try to control anxiety or stress. Without professional treatment, officers who engage in hazardous alcohol consumption may be negatively affected by reduced productivity at work, increased mental health concerns, and dysfunctional family and/or social environments. It is critical that officers learn healthy coping strategies to minimize stress on a regular basis, rather than attempt to mask stress with alcohol.

The Hazelden Betty Ford Experience

The Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation offers a number of inpatient and outpatient treatment options for alcohol abuse and dependence that are aligned with current research and focus on overall wellness and developing coping strategies for stress. To specifically meet the needs of law enforcement officers, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation hosts "Keeping the Force Strong," a day-long educational forum for police officers that focuses on special issues related to officers and addiction, while also highlighting treatment methods that have been proven effective in a police population.

Questions & Controversies

How can police officers get help for alcohol abuse without repercussions?

Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) are a fantastic first stop for police officers seeking treatment for alcohol use disorders. Law enforcement EAPs are generally developed to maintain high confidentiality in order to eliminate internal stigma or repercussions. Additionally, community-based groups such as AA provide a discrete and safe environment in a Twelve Step model that has been shown through research to be effective for police officers.14

How can officers maintain strong social ties with colleagues without drinking?

Departments that have established a "culture of alcohol" can make it difficult to maintain close ties without drinking. To help shift local culture away from one that relies on unhealthy alcohol consumption, officers can encourage their EAPs to engage prevention specialists to provide education and intervention from within the agency. These programs are often more successful than outside consultants because they come from a trustworthy source. In addition to focusing on current coworkers, officers should keep an eye to the future. Many young police officers report that they are under the greatest pressure to fit in with their veteran colleagues by drinking, so by setting a new example for rookies within your organization, you can play a critical role in ensuring that the future of your unit is not built upon a culture of alcohol.

How to Use This Information

Law Enforcement Administrators: Education on hazardous alcohol consumption and daily coping strategies for work-related stress can significantly assist officers with managing their stress levels and drinking behaviors. The Law Enforcement Families Partnership (LEFP), which was developed by Florida State University to reduce domestic violence among police officers, offers no-cost training strategies and curricula on their website, as well as guidance for reducing alcohol consumption among officers.

Officers: Do your part to encourage a cultural norm among your colleagues that is not dependent on alcohol use. In addition to self-care following a critical incident, it is important to self-monitor daily stress levels and find healthy coping strategies for minimizing stress related to day-to-day struggles. If you are regularly anxious or depressed as a result of your work, contact a counselor through your department's EAP to process these feelings in a healthy way.

Summary

Police officers are a unique subset of the population as a result of their occupational culture and regular exposure to stressors and trauma. These issues culminate in an increased risk for problem drinking, either as a result of social pressure or as an unhealthy way to try to control anxiety or stress. Without professional treatment, officers who engage in hazardous alcohol consumption can be negatively affected by reduced productivity at work, increases in mental health concerns, and dysfunctional family and/or social environments. It is critical that officers learn healthy coping strategies to minimize stress on a regular basis, rather than attempt to mask stress with alcohol.

References

- Ballenger, J. F., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Wasserman, D. A., Mohr, D. C., Liberman, . . . Marmar, C. R. (2010). Patterns and predictors of alcohol use in male and female urban police officers. The American Journal on Addictions, 20, 21–29.

- Lindsay, V., & Shelley, K. (2009). Social and stress-related influences of police officers' alcohol consumption. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 24, 8–92.

- Davey, J. D., Obst, P. L., & Sheehan, M. C. (2001). It goes with the job: Officers' insights into the impact of stress and culture on alcohol consumption within the policing occupation. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 8(2), 141–149.

- Bentel, D. J., & Smith, D. E. (1971). Drug abuse in combat: The crisis of drugs and addiction among American troops in Vietnam. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 4(1), 23–30.

- Greden, J. F., Frenkel, S. I., & Morgan, D. W. (1975). Alcohol use in the Army: Patterns and associated behaviors. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 132(1), 11–16.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Pietrzak, R. H., Goldstein, R. B., Southwick, S. M., & Grant, B. F. (2011). Prevalence and axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: Results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 456–465.

- Mitchell, J. T., & Everly, G. S., Jr. (2001). The basic critical incident stress management course: Basic group crisis intervention (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: International Critical Incident Stress Foundation.

- Cross, C. L., & Aschley, L. (2004 October). Police trauma and addiction: Coping with the dangers of the job. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin.

- Violanti, J. M. (2006). The police: Perspectives on trauma and resiliency. Traumatology, 12(3), 167–169.

- Berger, W., Coutinho, E. S. F., Figueira, I., Marques-Portella, C., Luz, M. P., Neylan, T. C., . . . Mendlowicz, M. V. (2012). Rescuers at risk: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of the worldwide current prevalence and correlates of PTSD in rescue workers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 1001–1011.

- Liberman, A. M., Best, S. R., Metzler, T. J., Fagan, J. A., Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (2002). Routine occupational stress and psychological distress in police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 25(2), 421–441.

- Swatt, M. L., Gibson, C. L., & Piquero, N. L. (2007). Exploring the utility of general strain theory in explaining problematic alcohol consumption by police officers. Journal of Criminal Justice, 35(6), 596–611.

- Kurke, M. I., & Scrivner, E. M. (2013). Police psychology into the 21st century. New York: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Eiserer, T. (2012 January 12). They drink when they're blue: Stress, peer pressure contribute to police's alcohol culture. The Dallas Morning News.