Problem Drinking Behaviors among College Students

Butler Center for Research - May 1, 2016

A Detriment to Students' Health and Education

Download the Problem Drinking Behaviors Among College Students Research Update.

Problematic drinking behaviors, such as frequent intoxication and binge drinking, have long been assumed to be more prevalent among college students than the general population. Researchers have dedicated several decades to better understanding problem drinking among college students and helping to prevent the serious consequences of this behavior.

Prevalence of Problem Drinking Among College Students

In a 2012 national survey conducted by the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, 41% of male college students reported that in the previous two weeks they had one or more episodes where they consumed five or more drinks in a row; 34% of female college students reported the same.1 While these high rates certainly indicate a need for intervention, many policy makers and scientists have wondered whether increased binge drinking patterns are unique to college students or indicative of all young adults within this age group. Without a clear understanding of the underlying issue, intervention efforts can be ineffective at improving the problem.

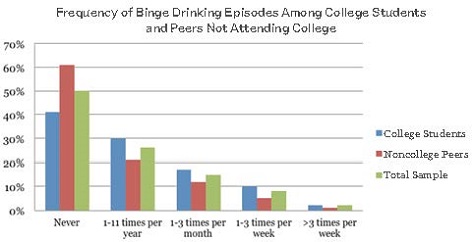

Historically, studies examining binge drinking between college students and young adults in the same age group who are not attending college have had mixed results.2 While college students have always tended to report higher rates of heavy drinking, it is often attributed to uncontrolled confounds, such as subject background and living arrangements; when these effects are controlled for, the significant association between college attendance and increased drinking is sometimes lost.3 A recent twin study provided strong evidence that college attendance did indeed correlate with significantly higher volumes of alcohol consumed, including binge drinking (see figure); although, when controlling for demographic and lifestyle characteristics, overall frequency of drinking and frequency of binge drinking were no longer significantly correlated with college attendance.2 There remained, however, a significant association between frequency of intoxication and college attendance, even when carefully controlling for demographic, biological, and social characteristics.2 These findings indicate that cultural norms specific to college campuses across the United States may encourage drinking to intoxication, more so than cultural norms among other young adult peer groups not attending college.

Consequences of Problem Drinking

Whether problematic drinking behaviors are uniquely correlated to college attendance or a result of a combination of demographic and lifestyle factors shared by students attending college, they pose a significant risk. An investigation of alcohol-related incidents among young adults found that in 2005, there was a total of 5,534 alcohol-related injury deaths among 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States; 1,825 (32.9%) of those who died were college students.4 In 2001, an estimated 599,000 college students sustained an alcohol-related injury, 646,000 were assaulted by another student who had been drinking, and 97,000 were victims of sexual assault or rape perpetrated by a student who had been drinking.5 More than 36% of students attending colleges with widespread patterns of heavy drinking admitted to driving after drinking in 2005, and nearly 15% reported driving after consuming five or more drinks.6 In addition to serious physical and legal consequences, college students who reported recent heavy drinking behavior also endorsed consequences that included missing classes, falling behind in school work, having unprotected sex, and damaging property.6

Strategies to Decrease Problem Drinking at Colleges

Given the wide range of factors that contribute to problem drinking risk among college students, developing content and strategies for intervention is an extremely difficult challenge. The majority of recent and historical research on heavy drinking among college students agrees that social and lifestyle factors are extremely influential in predicting drinking behaviors and outcomes, and these areas should be addressed in any intervention.2,7 Alcohol consumption has been significantly predicted by fraternity/sorority membership, the established and perceived social norms related to drinking, and beliefs that alcohol consumption will positively enhance experiences or increase conformity to one’s peers.7

With so many of these factors interacting and affecting drinking behavior, success of current interventions to address and prevent problem drinking is often more of a function of the individual who is receiving the intervention rather than the intervention itself.8, 9, 10 Researchers have found that women, upperclassmen, students who began drinking later in life, students who do not participate in drinking games, and those without social norms aligned with heavy drinking are the most responsive to interventions.9 More research is needed on strategies that better engage and support young, male students who regularly interact with a social environment that enables or glorifies problem drinking.9 It is recommended that any intervention should aim to address students at an individualized level that considers environmental, personality/psycho-pathological, and cognitive aspects related to heavy drinking.10

Despite the significant influence of individual student characteristics, some strategies have been found to be generally more effective than others. The impact of social norms across studies demonstrates the importance of incorporating peers and family members in interventions.7 By correcting inflated perceptions of peer and parent approval of heavy drinking, these interventions can make a considerable impact on the effect of social norms on alcohol consumption.7 Students who have experienced serious medical or legal consequences as a result of their drinking have been found to be responsive to brief motivational interviews,8 and all students demonstrate better outcomes following face-to-face interventions as compared to computer-administered interventions.11 The effects of most interventions tend to fade significantly over the year following the intervention, which indicates the need for follow-up after the initial administration.9

The Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation Experience

Tribeca Twelve

Research shows that problem drinking among young adults, especially young adults who are attending college, is strongly linked to cultural and environmental factors. Living arrangements and social environments that do not encourage or glorify heavy drinking have been shown to significantly decrease the likelihood of students engaging in unhealthy and dangerous drinking behavior. Tribeca Twelve is a vibrant sober living community specifically geared toward young adults between the ages of 18 and 29. Tribeca Twelve offers a warm and welcoming atmosphere in a beautiful Manhattan apartment complex for young adults who are transitioning out of inpatient treatment or who are participating in an outpatient treatment program.

MyStudentBody

MyStudentBody is a comprehensive approach to reducing the risk of drug and alcohol abuse and sexual violence among college students. MyStudentBody engages students and parents in effective, evidence-based prevention and gives administrators the data to target, evaluate, and strengthen prevention initiatives.

How to Use This Information

University Officials: Problem drinking among college students is heavily influenced by cultural factors, and universities that foster a heavy drinking atmosphere often face more common and more severe consequences of heavy drinking than campuses that do not have a heavy drinking culture.6 Working with professional organizations to implement evidence-based intervention and prevention strategies can be a great way to reduce the perception of problem drinking norms at your university.

Parents: Studies have shown that parent involvement in problem drinking interventions, as well as in establishing clear parental disapproval for heavy drinking, can be effective in reducing problem drinking among college students.8 It is important to foster a home environment where heavy drinking is clearly not the norm. Students who do not report actual or perceived parental approval of heavy drinking are much less likely to develop problem drinking behaviors in college.

References

- Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2013). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2012, volume I: Secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research.

- Slutske, W. S., Hunt-Carter, E. E., Nabors-Oberg, R. E., Sher, K. J., Bucholz, K. K., Madden, P. A. F., … Heath, A. C. (2004). Do college students drink more than their non-college-attending peers? Evidence from a population-based longitudinal female twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 133(4), 530-540.

- Gfroerer, J. C., Greenblatt, J. C., & Wright, D. A. (1997). Substance use in the U.S. college-age population: Differences according to educational status and living arrangement. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 62-65.

- Hingston, R. W., Zha, W., & Weitzman, E. R. (2009). Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 16, 12-20.

- Hingston, R., Heeren, T., Winter, M., & Wechsler, H. (2005). Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 259-279.

- Nelson, T. F., Xuan, Z., Lee, H., Weitzman, E. R., & Wechsler, H. (2009). Persistence of heavy drinking and ensuing consequences at heavy drinking colleges. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70, 726-734.

- Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N., & Larimer, M. E. (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 556-565.

- Mun, E. Y., White, H. R., & Morgan, T. J. (2009). Individual and situational factors that influence the efficacy of personalized feedback substance use interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 88-102.

- Henson, J. M., Pearson, M. R., & Carey, K. B. (2015). Defining and characterizing differences in college alcohol intervention efficacy: A growth mixture modeling application. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(2), 370-381.

- Ham, L. S. & Hope, D. A. (2003). College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 719-759.

- Carey, K. B., Scott-Sheldon, L. A., Elliott, J. C., Garey, L., & Carey, M. P. (2012). Face-to-face versus computer-delivered alcohol interventions for college drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 1998 to 2010. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(8), 690-703.