Psychedelics as Therapeutic Treatment

Butler Center for Research - September 2022

Introduction

Download the Psychedelics as Therapeutic Treatment Research Update.

In 2020, one in five adults in the United States experienced a mental illness; one in 15 adults experienced both a substance use disorder and mental illness.1 Thirty-seven percent of U.S. prisoners and 44 percent of jail inmates had been told in the past by a mental health professional that they had a mental disorder.2 The total economic burden of depression in the U.S. is estimated to be $210.5 billion per year.3 The heavy toll that mental health conditions take on individuals, communities, and the country at large has driven the search for new options for treatment. An option gaining more attention in recent years is the use of psychedelics in treatment.

What Are Psychedelic Drugs?

Psychedelic drugs or serotonergic hallucinogens are psychoactive substances that alter perceptions, mood, and cognitive processes.4 They are generally considered safer than other drugs such as opioids as they are not associated with compulsive drug-seeking behaviors.5

However, consumption of psychedelic drugs can rapidly produce a tolerance known as tachyphylaxis.4 Some studies have noted that cross-tolerance can occur between mescaline and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), as well as psilocybin and LSD. Additionally, despite the name hallucinogens, the users' experience does not always include hallucinations.6

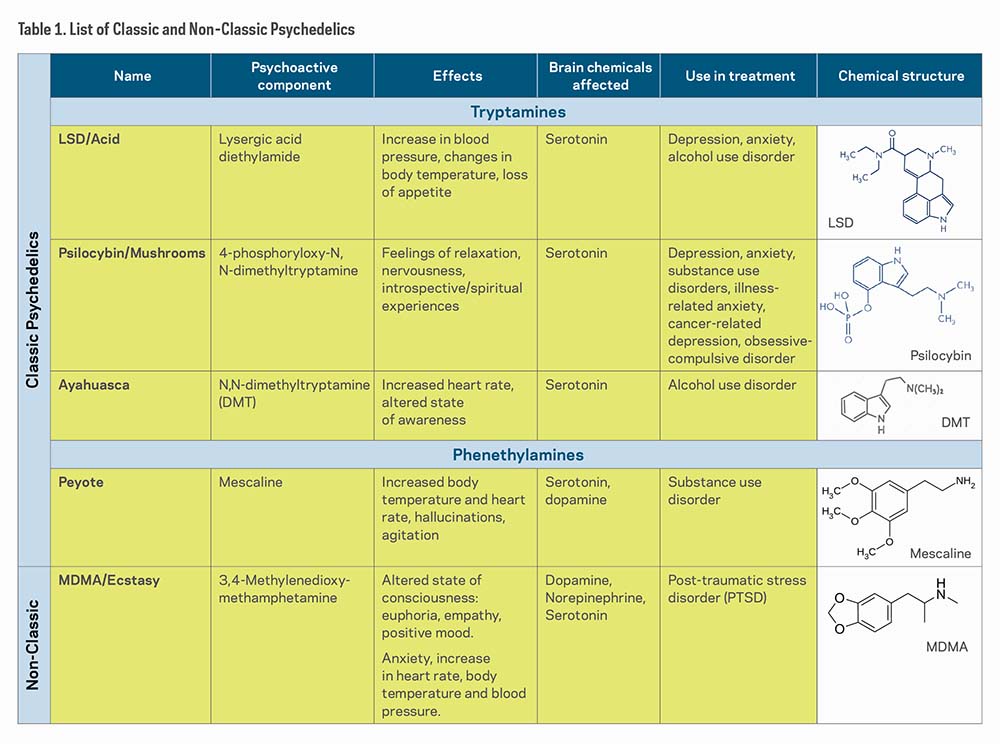

Psychedelic drugs are categorized into four classes based on chemical compounds and pharmacological profile: classic psychedelics, empathogens/entactogens, dissociative anesthetic agents, and atypical hallucinogens.5 For the sake of brevity, this research update will explore classic psychedelics and the non-classic psychedelic3,4 Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA).

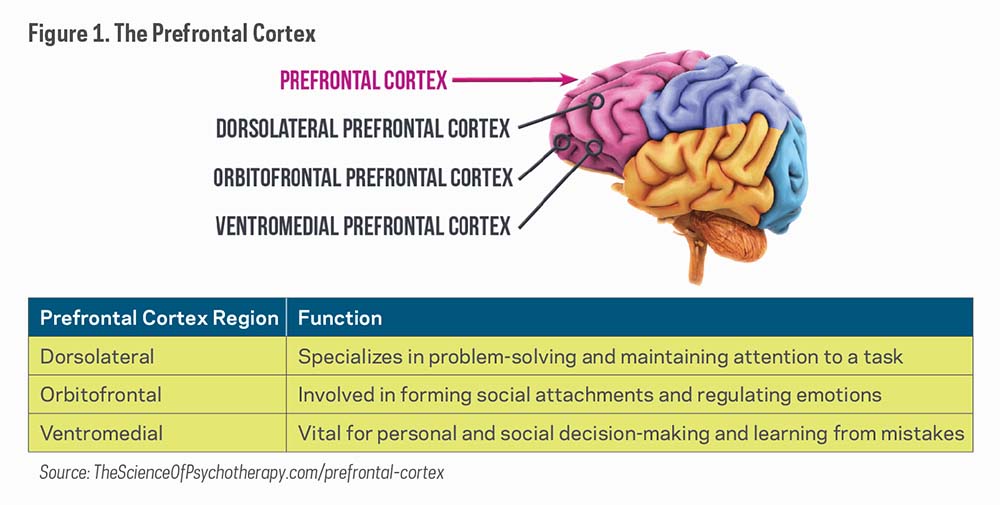

Classic psychedelics act as agonists (substances that bind to and cause activation of a receptor) or partial agonists of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, thus earning the "serotonergic" term. The most prominent effects are produced in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, which involves mood, cognition, and perception.7

Table 1 shows a list of "classic psychedelics," which includes LSD, Psilocybin, Ayahuasca (DMT), and Peyote (Mescaline), and one "non-classic psychedelic," MDMA/Ecstasy. Although all of these substances affect the brains' serotonin receptors, researchers have found that they affect other neural receptors and regions as well.

Brief History of the Use of Psychedelics in the Treatment of Mental Health Disorders

The use of psychedelics, particularly LSD, became more widely used by psychologists and psychiatrists in research and clinical practice during the 1950s and 1960s with studies showing supportive results regarding the use of psychedelics in the treatment of personality disorders,8 alcohol use disorder (AUD),9 and neurosis.10 However, their use did not prove effective in studies focused on people living with psychosis or schizophrenia.10 Although these studies contributed to the research of psychedelics today, the methods presented several problems including a lack of reporting of adverse outcomes, lack of control groups, and absence of statistical analyses.10 And in 1971, Abuzzahab and Anderson reviewed 31 studies on the psychedelic treatment model on AUD with LSD. They concluded that it was difficult to reach any meaningful generalizations due to the variety of published investigations with different designs and the various criteria used to measure improvement.11

Hallucinogenic studies were discontinued after these psychedelics were classified under Schedule I of the 1967 UN Convention on Drugs, legally defining them as having no accepted medical use and the maximum potential for harm and dependence10 and then the initiation of the U. S. federal Controlled Substances Act, signed by President Nixon in 1970.12 Consequently, the study of psychedelic drugs became practically impossible.10

Modern-Era Research

In the 1990s, three studies examined the effects of mescaline (Germany, 1998), DMT (ayahuasca) (United States, 1994), and psilocybin (Switzerland, 1997) on healthy individuals, which led to the revival of psychedelic studies.10 These studies helped to establish the safety of using these psychedelic drugs on human subjects for research purposes. Additionally, in 1994, U.S. researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial to inform safe dosing of MDMA.5 Subsequent trials conducted in the 2000s explored MDMA's effects on emotional processing, PTSD, anxiety, and social anxiety.5 The results of the studies helped researchers identify MDMA as safe enough to use in future research.5

Mood and Anxiety Disorders

In 2006, Moreno and colleagues recruited nine treatment resistant patients who met DSM-IV criteria for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) for a modified double-blind study on psilocybin's treatment efficacy, tolerability and safety.13 Participants were given up to four administrations of psilocybin separated by at least one week. Low, medium, and high doses were assigned in that order, with a very low dose inserted randomly after the first low dose. Decreases in OCD symptoms score were observed in all nine subjects at one or more of the testing sessions.13 Limitations of the study include the small sample size and that the modified escalating dosing method may have influenced expectations in both participants and researchers.

In an open-label trial (where study participants and researchers both know which treatment the patient is receiving), researchers wanted to assess the antidepressive potentials of ayahuasca.14 Conducted in an inpatient psychiatric unit, 17 patients with recurrent major depressive disorder received one oral dose of ayahuasca. Their symptoms were assessed at baseline and again at 1, 7, 14, and 21 days post treatment. Significant decreases in scores of depression and scores of anxious-depression were observed at all points of assessment post treatment.14 As this was not a randomized or double-blind study, and there was no placebo or other comparator group, it cannot be concluded that the observed changes were in fact caused by ayahuasca.

Ayahuasca was also tested with 29 patients diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder.15 Participants were randomized to either placebo or one dose of freeze-dried ayahuasca brew. None of the patients had any prior use of ayahuasca, and all participants were weaned off their antidepressant medications prior to drug administration. Significant antidepressant effects of ayahuasca were observed when compared with the placebo group from baseline to 7 days after dosing.15 Although results seem promising, the number of participants was small and therefore randomized trials in larger populations are necessary. Also, the study was limited to patients with treatment-resistance depression which prevents an extension of these results to other types of depression.

In a London-based open-label, uncontrolled study by Carhart-Harris and colleagues, 20 patients with moderate or severe major treatment-resistant depression each received two doses of psilocybin.16 All participants had a history of unsuccessful treatment of no less than two different anti-depressant medications. Psilocybin was administered at a moderate dose, and one week later followed by a high dose. Marked reductions in depressive symptoms were observed for the first 5 weeks post-treatment, and results remained positive at 3 and 6 months.16 As this was an open-label trial with no control condition, limited conclusions can be drawn about treatment efficacy. Further research utilizing double-blind randomized control trials are needed.

Substance Use Disorder

Bogenschutz and colleagues, in a proof-of-concept study, assessed the effect of psilocybin treatment in 10 patients with DSM-IV-established diagnosis of alcohol dependence.17 Psilocybin was given at two separate occasions, first at week 4 (moderate-high dose) and again at week 8 (high dose) in addition to 12 weeks of Motivational Enhancement Therapy. The change in drinking behavior (change in percent heavy drinking days) served as the primary study outcome. Abstinence did not increase significantly in the first 4 weeks of treatment, before participants had received psilocybin, but increased significantly following psilocybin administration.17 Limitations of this study include small sample size, lack of a control group, and lack of biological verification of alcohol use.

In another study, researchers examined the feasibility and safety of using psilocybin treatment to treat smoking dependence.18 Fifteen nicotine-dependent smokers were included in the trial. The study consisted of a 15-week course of smoking cessation treatment. Participants attended four weekly meetings during which Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy was delivered. At week 5, participants were administered a moderate dose of psilocybin. Participants continued meeting weekly with study staff and received another dose of psilocybin at week 7 and optionally again at week 13. Changes in smoking between study intake and 6-month follow-up were examined using biomarkers and self-reports of cigarettes per day. At 6 months' follow-up, 12 of the 15 participants were abstinent, and compared to baseline, all participants showed significant reductions in self-reported daily smoking, urine cotinine, and breath carbon monoxide at this time point.18 In a follow-up paper by the same authors, 67% (10/15) of the participants were still abstinent after 12-months (confirmed by levels of urine cotinine and breath carbon monoxide) with 9 of them abstinent at subsequent long-term follow-up (mean 30 months post-first psilocybin session). Seven of the nine reported continuous abstinence since first psilocybin session.19 However, the small sample size and the open-label design of the original study and the follow-up paper does not allow for definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of psilocybin.

Lastly, in 2019, Garcia-Romeu and colleagues investigated instances in which naturalistic psychedelic use led to self-reported reductions in alcohol misuse outside a formal treatment setting.20 Researchers recruited participants for an anonymous online survey through ads posted on social media and drug discussion websites over a period of about 2 years. Participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria: 18 years or older, fluent in English, have met DSM-5 criteria for AUD in the past and had used a classic psychedelic (outside of a university or medical setting), followed by reduction or cessation of subsequent alcohol use. The final sample size included 343 adults, predominantly White males from the U.S., whose alcohol use was assessed retrospectively before and after their use of a psychedelic. This included items rating distress related to alcohol use prior to psychedelic use, overall duration of alcohol misuse, use of medication or other AUD treatments before and after psychedelic use, age of first alcohol use, and lifetime presence of other mental health diagnoses. Participants also completed two iterations of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C), the DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder Symptom Checklist, and the Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ). Alcohol and cannabis were the most heavily used substances, according to self-reported lifetime drug use history, and the most commonly used classic psychedelics were psilocybin or LSD. Findings indicate that after naturalistic use of psychedelics, most participants reported reduced alcohol use and the majority no longer met the criteria for AUD.20 Participants also reported that they experienced fewer withdrawal symptoms than in previous attempts to quit drinking after their use of psychedelics.20 Results from this study are limited due to participant self-selection, volunteer bias, and the retrospective nature of the data, which are subject to recall bias.

The Future of Psychedelics in Research

Given the mixed research findings, it is important to proceed with care and focus on scientific rigor and transparency. There is a need to better establish which of these drugs are most effective, how they should be administered, and who is most likely to benefit. New and future research efforts may benefit from exploring the underlying therapeutic mechanisms of the chemical component(s) of psychedelics in the brain. Such studies could facilitate the development of personalized medicines in the treatment of behavioral health disorders and provide needed data on potential abuse or side effects. Additionally, future studies can increase generalizability by recruiting subjects from diverse populations and expanding the sample size. As mentioned, most studies recruited relatively small samples which prevents applicability in other research settings.

Lastly, there is a need for clinical studies to improve the rigor of the research study methods. For example, additional studies utilizing double-blinded and placebo designs would improve the ability to make causal inferences from study results. Moreover, longitudinal research studies would increase our understanding of long-term use and long-term consequences associated with use of psychedelic drugs.

Conclusion

Finding long-lasting treatment options for mental health disorders, including addiction, is complicated and met with various challenges. Therefore, more treatment options are being explored. The use of psychedelics in treatment is getting more attention as recent research suggests efficacious treatment outcomes in specific behavioral health disorders. However, it is important to note the limitations of these studies.

How To Use This Information

It is important to find long-lasting treatment options for addiction and mental health disorders. While more research is being conducted on the use of psychedelics as therapeutic treatment, it is vital to move ahead with care and to focus on the scientific rigor of the research. Current research has not found consistent evidence of effectiveness. Further clinical research is necessary to establish which psychedelic drugs are most effective, how they should be administered, and who is most likely to benefit. It is crucial for treatment providers and others to be aware of the current state of research in order to have informed conversations with their clients and provide the best care possible.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/ 2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf

- Bronson, J., & Berzofsky, M. (2017). Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics. bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf

- Greenberg, P. E., Fournier, A-A., Sisitsky, T., Pike, C. T., & Kessler, R. C. (2015). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(2), 155–162. doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09298

- Nichols, D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 68(2), 264–355. doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

- Reiff, C. M., Richman, E. E., Nemeroff, C. B., Carpenter, L. L., Widge, A. S., Rodriguez, C. I., Kalin, N. H., McDonald, W. M., & The Work Group on Biomarkers and Novel Treatments, a Division of the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research. (2020). Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(5), 391–410. doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010035

- Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. (2017). Metabolism of psilocybin and psilocin: Clinical and forensic toxicological relevance. Drug Metabolism Reviews, 49(1), 84–91. doi.org/10.1080/03602532.2016.1278228

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). How do hallucinogens (LSD, psilocybin, peyote, DMT, and ayahuasca) affect the brain and body? nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/hallucinogens-dissociative -drugs/how-do-hallucinogens-lsd-psilocybin-peyote-dmt-ayahuasca-affect-brain-body

- Chandler, A. L., & Hartman, M. A. (1960). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) as a facilitating agent in psychotherapy. American Medical Association Archives of General Psychiatry, 2(3), 286–299. doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1960.03590090042008

- MacLean, J. R., MacDonald, D. C., Byrne, U. P., & Hubbard, A. M. (1961). The use of LSD-25 in the treatment of alcoholism and other psychiatric problems. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 22(1), 34–45. jsad.com/doi/10.15288/qjsa.1961.22.034

- Rucker, J. J. H., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2018). Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200–18. doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.040

- Abuzzahab, F. S., & Anderson, B. J. (1971). A review of LSD treatment in alcoholism. International Pharmacopsychiatry, 6(4), 223–235. doi.org/10.1159/000468273

- Bogenschutz, M. P., & Forcehimes, A. A. (2016). Development of a psychotherapeutic model for psilocybin-assisted treatment of alcoholism. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(4), 389–414. doi.org/10.1177/0022167816673493

- Moreno, F. A., Wiegand, C. B., Keolani Taitano, E., & Delgado, P. L. (2006). Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in 9 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(11), 1735–1740. doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v67n1110

- Sanches, R. F., de Lima Osório, F., dos Santos, R. G., Macedo, L. R. H., Maia-de-Oliveira, J. P., Wichert-Ana, L., de Araujo, D. B., Riba, J., Crippa, J. A., & Hallak, J. E. C. (2016). Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: A SPECT study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 36(1), 77–81. doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000000436

- Palhano-Fontes, F., Barreto, D., Onias, H., Andrade, K. C., Novaes, M. M., Pessoa, J. A., Mota-Rolim, S. A., Osório, F. L., Sanches, R., dos Santos, R. G.,

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Day, C. M. J., Rucker, J., Watts, R., Erritzoe, D. E., Kaelen, M., Giribaldi, B., Bloomfield, M., Pilling, S., Rickard, J. A.,

- Bogenschutz, M. P., Forcehimes, A. A., Pommy, J. A., Wilcox, C. E., Barbosa, P. C. R., & Strassman, R. J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(3), 289–299. doi.org/10.1177/0269881114565144

- Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., Cosimano, M. P., & Griffiths, R. R. (2014). Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(11), 983–992. doi.org/10.1177/0269881114548296

- Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(1), 55–60. doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135

- Garcia-Romeu, A., Davis, A. K., Erowid, F., Erowid, E., Griffiths, R. R., & Johnson, M. W. (2019). Cessation and reduction in alcohol consumption and misuse after psychedelic use. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 33(9), 1088–1101. doi.org/10.1177/0269881119845793