Women and Substance Abuse

Butler Center for Research - July 1, 2015

Gender Differences in Addiction

Download the Research Update Women and Substance Abuse.

The consideration of gender differences in substance use and abuse, addiction, and treatment outcomes has grown exponentially in the scientific literature since the release of the National Institutes of Health Policy and Guidelines on the Inclusion of Women and Minorities as Subjects in Clinical Research in 1994.1 As a result, researchers have uncovered a number of critical differences between men and women in what was once predominantly believed to be a "male issue,"2 including differences related to addiction treatment and outcomes.

Since the late 1980s, it has been observed that for drugs such as marijuana, opioids, and cocaine, women reach higher levels of substance abuse and addiction severity with smaller amounts and shorter time of use than their male counterparts.1, 3, 4 This effect is also present for alcohol abuse and addiction.4, 5, 6 As a result of physiological differences related to the processing of alcohol, women are more likely to become intoxicated on lower doses of alcohol than men.7 In addition, women who drink regularly are more prone to the physiological consequences of alcohol abuse than men, facing increased risks for health problems that include cirrhosis, heart damage, and brain damage.8, 9

Mental Health Considerations

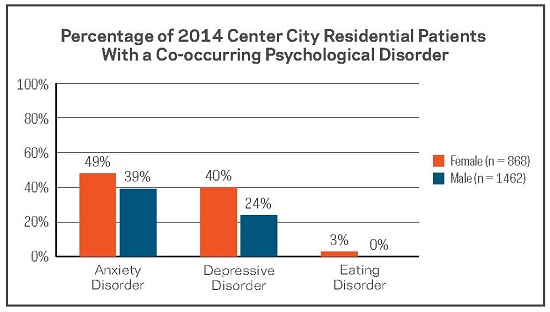

Co-occurring mental health disorders have a significant impact on substance use and abuse and can also significantly impact treatment for chemical dependence.10 This is an especially serious issue for women, who have been shown to present an elevated risk for comorbidity of addiction with affective and anxiety disorders.11, 12 This effect is also supported by patient data from Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation treatment centers. The Butler Center for Research recently completed an analysis of co-occurring mental health disorders for patients who were admitted for residential treatment at the Center City, Minnesota, location in 2014. Women were significantly more likely than men to have a co-occurring depressive or anxiety disorder and showed significantly higher numbers for co-occurring eating disorders as well. Findings of this analysis are presented in the graph below.

Substance Use Rates Among Women

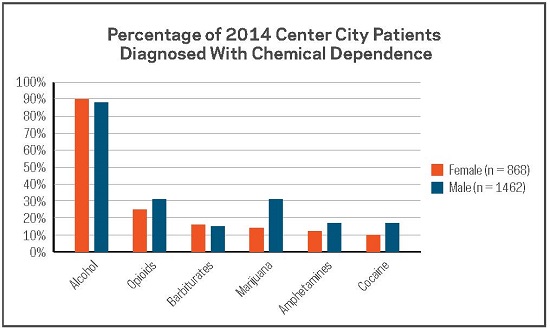

The majority of women who seek treatment with the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation do so for dependence on alcohol; the rate of dependence for other drugs is significantly lower. In fact, an analysis of patients who received treatment in 2014 shows that a higher percentage of female patients (90.44%) were diagnosed with alcohol dependence than male patients (87.62%). This is a particularly interesting finding, since higher percentages of male patients had dependence diagnoses for nearly every other drug type. The percentage of female patients diagnosed with barbiturate dependence was also slightly higher than the percentage of male patients, although the difference was not significant (see graph below).

The pattern of dependence diagnoses at the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation are similar to those reported for other agencies and show that alcohol dependence is the most common dependence diagnosis among women attending treatment. However, it is important to note that many women who have a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence have also been diagnosed as dependent on at least one other drug. Among women receiving treatment in Center City in 2014 who were diagnosed with alcohol dependence, 36.7% were also diagnosed with dependence on at least one other drug.

Summary

Substance abuse and addiction differences between men and women are complex. Research has uncovered a number of gender differences in physiology, psychology, and social factors related to addiction. As a result, it is critical to consider these differences when developing treatment plans and strategies, especially for the historically-under-represented female patient population, as a single generalized solution is often not the most effective.

The Hazelden Betty Ford Experience

In order to properly address treatment and addiction issues that are specific to a female population, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation opened the Betty Ford Women's Recovery Center on its Center City, Minnesota, campus in 2007. When women in residential treatment live on-site with other women and participate in women-only groups and activities, they can share experiences and aspects of addiction and recovery that are specific to women—a critical element of successful treatment for women with chemical dependence.

By opening our Betty Ford Women's Recovery Center, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation has been able to treat more women with drug and alcohol addiction and expand our mission to a larger population of those who are struggling with alcohol and drug dependence. From 2004 to 2006, our organization provided residential treatment to an average of 724 women per year. Since 2007, that number has risen to an average of 845 women per year.

Questions & Controversies

With its emphasis on powerlessness and male-oriented language, is Alcoholics Anonymous helpful for women in recovery?

Many research studies show that women regularly engage with Alcoholics Anonymous and other Twelve Step fellowships, particularly after receiving Twelve Step–based residential treatment, and are more likely to have positive substance use outcomes after treatment than women who do not affiliate with them.13, 14 Though many people believe that because AA was historically male-orientated women are discouraged from becoming involved, this is not supported by the data. In its 2007 membership survey, AA World Services reported that 33% of its current members were women.

How to Use This Information

Counselors and Practitioners: When treating addiction and understanding substance abuse behaviors with men and women, a one-size-fits-all model has been proven by the research to be ineffective. Women have specific needs and concerns that may not be addressed by a gender-neutral treatment model. It is critical to familiarize yourself with common gender-specific differences related to addiction and incorporate these elements into your treatment plan for female patients.

References

1. Greenfield, S. F., Brooks, A. J., Gordon, S. M., Green, C. A., Kropp, F., McHugh, K., . . . Miele, G. M. (2007). Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86(1), 1–21.

2. Wilke, D. (1994). Women and alcoholism: How a male-as-norm bias affects research, assessment, and treatment. Health and Social Work, 19(1), 29–35.

3. Kosten, T. A., Gawin, F. H., Kosten, T. R., & Rounsaville, B. J. (1993). Gender differences in cocaine use and treatment response. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 10, 63–66.

4. Hernandez-Avila, C. A., Rounsaville, B. J., & Kranzler, H. R. (2004). Opioid-, cannabis-, and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 74, 265–272.

5. Schuckit, M. A., Anthenelli, R. M., Bucholz, K. K., Hesselbrock, V. M., & Tipp, J. (1995). The time course of development of alcohol-related problems in men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 56, 218–225.

6. Dawson, D. A. (1996). Gender differences in the probability of alcohol treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 8, 211–225.

7. Frezza, M., DiPadova, C., Pozzato, G., Terpin, M., Baraona, E., & Lieber, C. S. (1990). High blood alcohol levels in women: The role of decreased gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity and first-pass metabolism. New England Journal of Medicine, 322(2), 95–99.

8. Urbano-Márquez, A., Estruch, R., Fernández-Solá, J., Nicolás, J. M., Paré, J. C., & Rubin, E. (1995). The greater risk of alcoholic cardiomyopathy and myopathy in women compared with men. JAMA, 274(2), 149–154.

9. Mann, K., Ackerman, K., Croissant, B., Mundle, G., Nakovics, H., & Dielh, A. (2005). Neuroimaging of gender differences in alcohol dependence: Are women more vulnerable? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(5), 896–901.

10. Minkoff, K. (2001). Best practices: Developing standards of care for individuals with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services, 52(5), 597–599.

11. Hesselbrock, V. M., Hesselbrock, M. N., & Workman-Daniels, K. L. (1986). Effect of major depression and antisocial personality on alcoholism: Course and motivational patterns. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 47, 207–212.

12. Roy, A., DeJong, J., Lamparski, D., Adinoff, B., George, T., Moore, V. (1991). Mental disorders among alcoholics: Relationship to age of onset and cerebrospinal fluid neuropeptides. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 423–427.

13. Witbrodt, J., & Kaskutas, L. A. (2005). Does diagnosis matter? Differential effects of Twelve Step participation and social networks on abstinence. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31, 685–707.

14. Timko, C., Billow, R., & DeBenedetti, A. (2006). Determinants of Twelve Step group affiliation and moderation of the affiliation-abstinence relationship. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83, 111–121.