Beyond Binging: High-Intensity Drinking

Butler Center for Research

Overview

Alcohol is a major contributor to mortality and morbidity in the United States. An estimated 88,000 people die each year from alcohol-related causes (Stahre, Roeber, Kanny, Brewer, & Zhang, 2014), making it the fourth-leading cause of preventable death (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004). A recent analysis of national data showed that alcohol-related emergency department (ED) visits are increasing at a faster rate than overall ED visits, placing a huge burden on our already stressed health care system. Currently there are nearly 4 million alcohol-related ED visits per year in the United States, representing a significant increase since 2001 (Mullins, Mazer-Amirshahi, & Pines, 2017). Binge drinking—namely, consuming four or more drinks for females and five or more for males in one sitting—has been the focus of numerous studies during the past few decades, and the negative impact of binge drinking on individual health, safety and well-being is clearly understood. But the finding that a substantial proportion of young adults are engaging in levels of alcohol consumption beyond the “binge” threshold (or “high-intensity drinking”) is sparking new concerns among public health professionals.

Prevalence

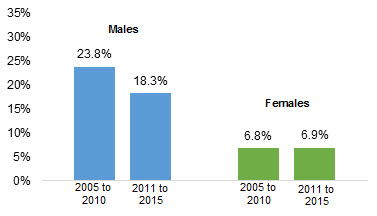

Nationally, almost one-third of college students engaged in binge drinking in 2015. Modest decreases have been observed in binge drinking since 2008, when the prevalence was closer to 40 percent (Johnston et al., 2016). But new concerns have been raised about high-intensity drinking, defined as alcohol consumption that is at least two times more than the binge threshold.1 About one in nine young adults (11 percent) were classified as high-intensity drinkers from 2005 to 2015. As seen in Figure 1 below, the prevalence of high-intensity drinking decreased among male college students from 2005 to 2015, and remained steady among female college students (Johnston et al., 2016). However, recent work by Patrick, Terry-McElrath, Kloska, & Schulenberg (2016b) found that high-intensity drinkers binge drink almost twice as frequently as those who do not engage in high-intensity drinking. And the lead author, Dr. Megan Patrick from the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research, said: “It was surprising to me that about half of the people we call binge drinkers, who meet the typical binge drinking criteria of having five or more drinks in a row, are actually drinking about twice as much alcohol as that. It became clear that high-intensity drinking—for example, drinking 10 or more drinks in a row—was more common than we thought.”

Figure 1. Prevalence of high-intensity drinking (10+ drinks on one occasion during the past two weeks), among college students (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2016)

Similar trends are observed among high school students as well. National data from 1991 to 2015 showed that more than half of high school drinkers binge drank, and 44 percent of binge drinkers consumed eight or more drinks in a row (Esser, Clayton, Demissie, Kanny, & Brewer, 2017).

“It is these high-intensity drinkers who reach dangerously high blood alcohol levels and are at the greatest risk for both acute and long-term consequences,” added Patrick.

Dr. Aaron White (2017) suspects that high-intensity drinking might be behind the rise in alcohol-related hospitalizations and deaths among young adults during the past few decades.

Demographics

White individuals are more likely than any other racial group to engage in high-intensity drinking (Terry-McElrath & Patrick, 2016). With respect to age, the prevalence of high-intensity drinking among young adults peaks between the ages of 21 and 22 and then steadily decreases with age (Johnston et al., 2016; Patrick et al., 2016b). Interestingly, college students do not differ from their non-college-attending peers with respect to the prevalence of high-intensity drinking (Johnston et al., 2016), but college students engage in high-intensity drinking more frequently than their non-college-attending peers (Patrick et al., 2016b).

Excessive Drinking Goes Hand in Hand With Other Drug Use, Including Marijuana

Decades of research studies support the notion that polysubstance use is the norm rather than the exception. For example, among a sample of 1,776 college undergraduates, Keith et al. (2015) found that students who use marijuana are much more likely to binge drink frequently than students who do not use marijuana. Excessive drinking behavior is associated with a higher risk for smoking cigarettes and using other illicit drugs as well (Keith et al., 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

Early Intervention Needed

Identifying and intervening with young people who engage in either binge drinking or high-intensity drinking is important because of the many acute and long-term health consequences of heavy alcohol consumption. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends that alcohol be consumed in moderation—up to one drink a day for women compared with two a day for men (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015). Not only are individuals who drink alcohol at levels exceeding these guidelines at risk for health and safety issues, but they might also experience problems academically, professionally and personally. Of note is a new study showing associations between high blood alcohol concentration and acute cardiovascular events, including having an irregular heartbeat (Brunner et al., in press).

Although early intervention can help set a young person back on track and reduce the risk for chronic problems, only 18 percent of binge drinkers are asked about alcohol use by their physician and advised to reduce their consumption (McKnight-Eily et al., 2017). More and earlier intervention is needed, said Dr. Amelia Arria, associate professor and director of the Center on Young Adult Health and Development at the University of Maryland School of Public Health.

“Regularly asking about alcohol consumption patterns to detect individuals at risk for problematic consumption should be common practice for physicians and other health care professionals who manage the care of young adults,” Arria said. “Early intervention to address problematic drinking trajectories is essential to mitigate possible health-related consequences.”

Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation Perspectives

Dr. Joseph Lee, Medical Director, Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation Youth Continuum:

“This research is another reminder that alcohol—as our most accessible and culturally acceptable drug—is the one that most often triggers problems in people who are susceptible to substance misuse, addiction, and other related health issues.”

“We are seeing more problems with college-educated women in particular, who are now drinking far more, and with greater consequence, than in previous generations.”

“Thousands of college students at low risk for developing alcohol use disorders still suffer from the ramifications of excessive drinking—from DUIs, car crashes, and violence, to date rape. Millions more are affected by the collateral damage.”

“Some people who drink to the extreme might also gravitate toward other risks, such as using other mood-altering substances.”

“People in high-risk populations, who often drink excessively in combination with other substance use, will likely develop severe alcohol use disorder and experience a host of other tragic consequences. Unfortunately, these high-risk individuals are rarely identified and helped, until it’s too late. Instead, they remain hidden in a popular culture that has both normalized problem drinking and failed to let go of the delusional thinking that everyone reacts to alcohol in the same way.”

Nick Motu, former Vice President, Hazelden Betty Ford Institute for Recovery Advocacy:

“Amid our country’s devastating opioid epidemic and heated debates over marijuana policy, it’s important to remember that alcohol remains America’s most pervasive drug and the one most harmful to public health and the economy. It contributes to almost 90,000 deaths annually and costs the country a quarter of a trillion dollars per year in medical and public safety expenses, and lost productivity.”

“Unfortunately, alcohol is ubiquitous in American culture, celebrated more than discouraged. We must address the culture by creating policies, communities, and environments that discourage drinking more and promote it less. We feel the policies and practices that have reduced tobacco use by more than 50 percent in the past 50 years offer some guidance on effective approaches.”

References

- Brunner, S., Herbel, R., Drobesch, C., Peters, A., Massberg, S., Kääb, S., & Sinner, M. F. (in press). Alcohol consumption, sinus tachycardia, and cardiac arrhythmias at the Munich Oktoberfest: Results from the Munich Beer Related Electrocardiogram Workup Study (MunichBREW). European Heart Journal.

- Esser, M. B., Clayton, H., Demissie, Z., Kanny, D., & Brewer, R. D. (2017). Current and binge drinking among high school students — United States, 1991–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(18), 474-478.

- Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Miech, R. A. (2016). Monitoring the Future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Volume 2, college students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

- Keith, D. R., Hart, C. L., McNeil, M. P., Silver, R., & Goodwin, R. D. (2015). Frequent marijuana use, binge drinking and mental health problems among undergraduates. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(6), 499-506.

- McKnight-Eily, L. R., Okoro, C. A., Mejia, R., Denny, C. H., Higgins-Biddle, J., Hungerford, D., Kanny, D., & Sniezek, J. E. (2017). Screening for excessive alcohol use and brief counseling of adults — 17 states and the District of Columbia, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(12), 313-319.

- Mullins, P. M., Mazer-Amirshahi, M., & Pines, J. M. (2017). Alcohol-related visits to US emergency departments, 2001–2011. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 52(1), 119-125.

- Patrick, M. E., Cronce, J. M., Fairlie, A. M., Atkins, D. C., & Lee, C. M. (2016a). Day-to-day variations in high-intensity drinking, expectancies, and positive and negative alcohol-related consequences. Addictive Behaviors, 58, 110-116.

- Patrick, M. E., Terry-McElrath, Y. M., Kloska, D. D., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2016b). High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: Prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(9), 1905-1912.

- Patrick, M. E., & Terry-McElrath, Y. M. (2017). High-intensity drinking by underage young adults in the United States. Addiction, 112(1), 82-93.

- Stahre, M., Roeber, J., Kanny, D., Brewer, R. D., & Zhang, X. (2014). Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Preventing Chronic Disease, 11, E109.

- Terry-McElrath, Y. M., & Patrick, M. E. (2016). Intoxication and binge and high-intensity drinking among US young adults in their mid-20s. Substance Abuse, 37(4), 597-605.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015). 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Retrieved from http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

- White, A. M., Kraus, C. L., & Swartzwelder, H. S. (2006). Many college freshmen drink at levels far beyond the binge threshold. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30(6), 1006-1010. dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00122.x

- White, A. M. (2017). Commentary on Patrick and colleagues: High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: Prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 41(2), 270-274. dx.doi.org/10.1111/acer.13306